IB Economics:

|

Supply-side policiesThe goals of supply-side policies:

|

SUPPLY-SIDE POLICIESSupply side policies aim to increase long term competitiveness and productivity. For example, it was hoped that privatisation and deregulation would make firms more productive and competitive. Therefore, in the long run supply side policies can help increase the level of employment in an economy as firms expand and grow. However, supply side policies work very much in the long term; they cannot be used to reduce sudden increases in the unemployment rate. Also, there is no guarantee government supply side policies will be successful in reducing unemployment.

Supply-side policies can involve interventionist supply side policies (e.g. government spending on education) or free market supply side policies (e.g. reduce government legislation). The main macro-economic objectives of the government include:

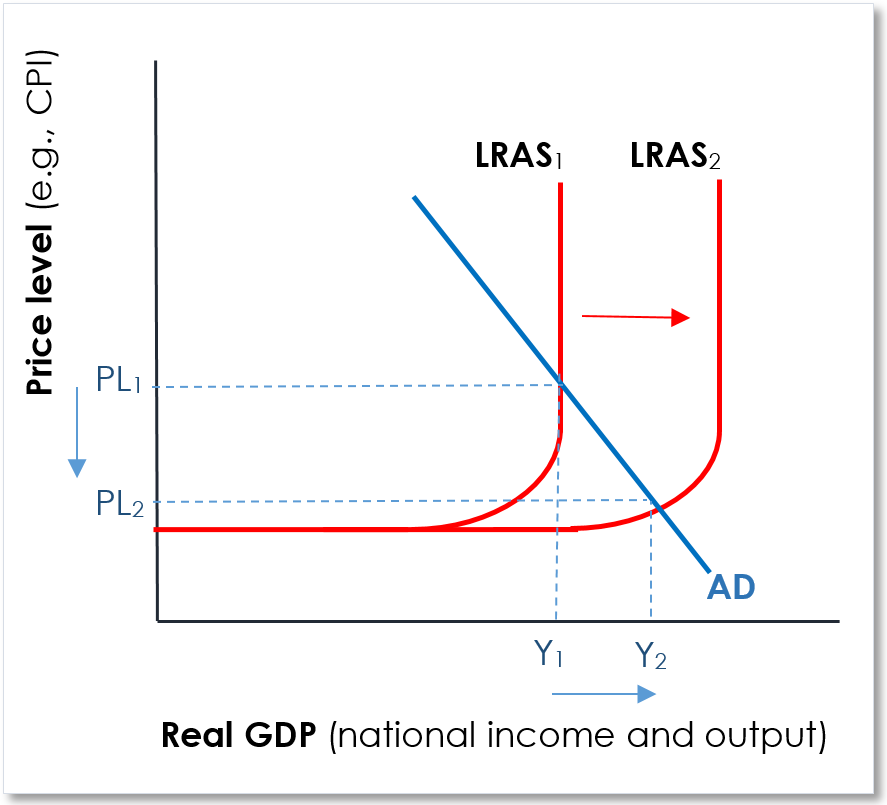

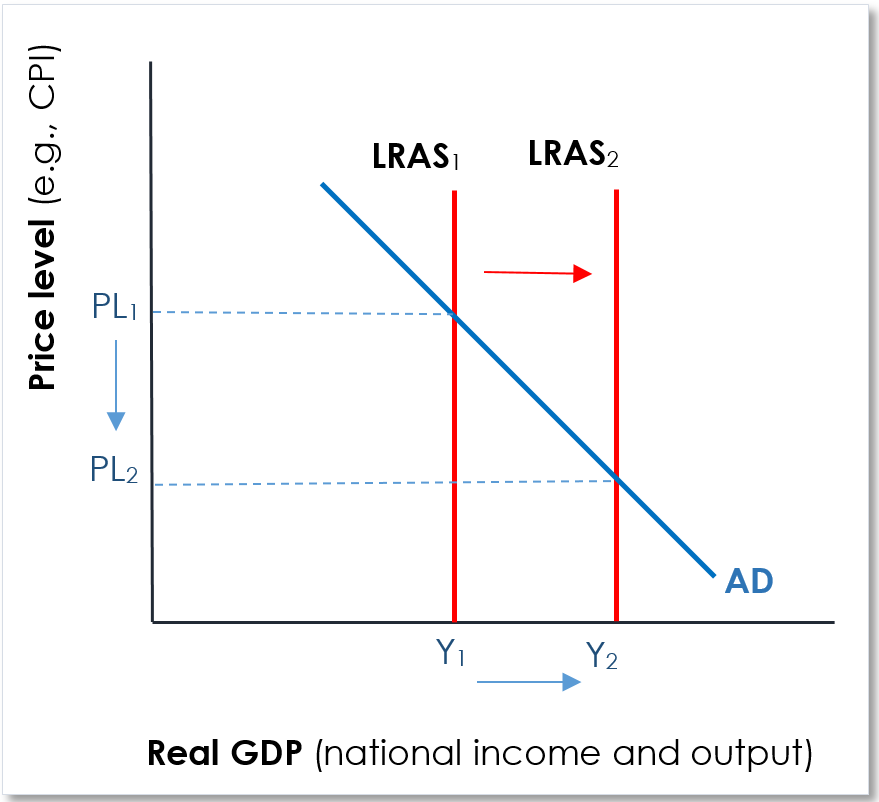

Quite often these objectives conflict with each other. For example, expansionary fiscal policy may contribute to higher economic growth and lower unemployment; however, it will be at the cost of inflation and a deterioration on the current account. To achieve all objectives simultaneously it is essential to improve the supply side of the economy. If the government can increase productivity and shift LRAS to the right (shown right), it can enable employment to grow and unemployment to fall without the inflationary pressures associated with increasing aggregate demand. To attain rates of low unemployment and inflation and increase economic growth, supply side policies can help reduce costs and increase productivity. For example, privatisation and deregulation can help reduce costs, lower costs increase the profitability of firms which, in turn, increase the supply of goods and services and employ more workers to do so. EXPLAINING SUPPLY-SIDE POLICIES |

WHAT ARE SUPPLY-SIDE POLICIES? |

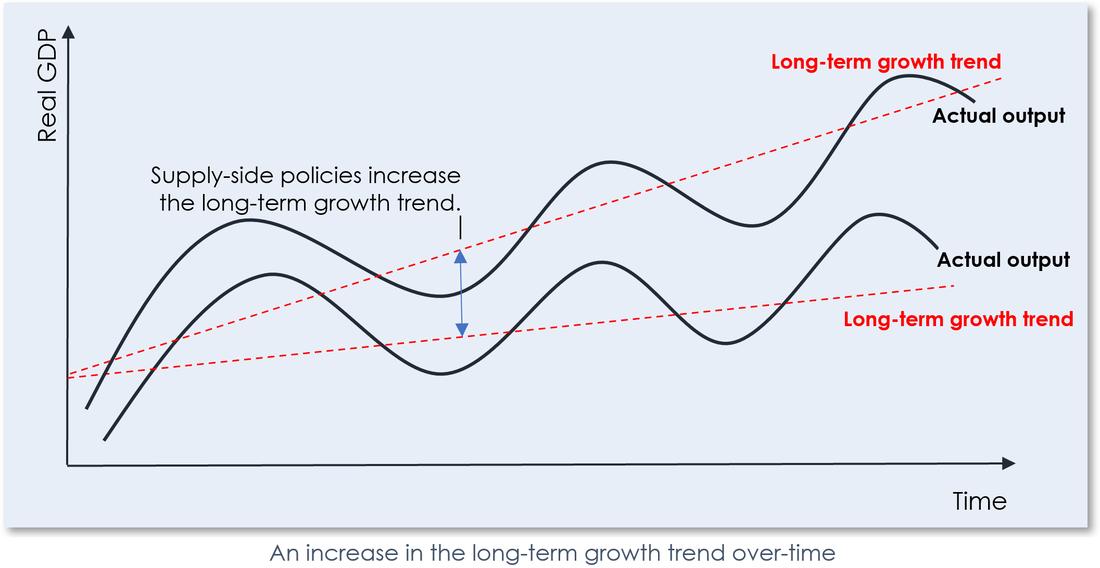

Goals of supply-side policiesIncreasing long-term growth by increasing the economy’s productive capacity.

The primary goal of supply-side macroeconomic policies is to increase the potential output of an economy. This can be modelled as either a:

Increasing firms’ incentives to invest in innovation by reducing costs.

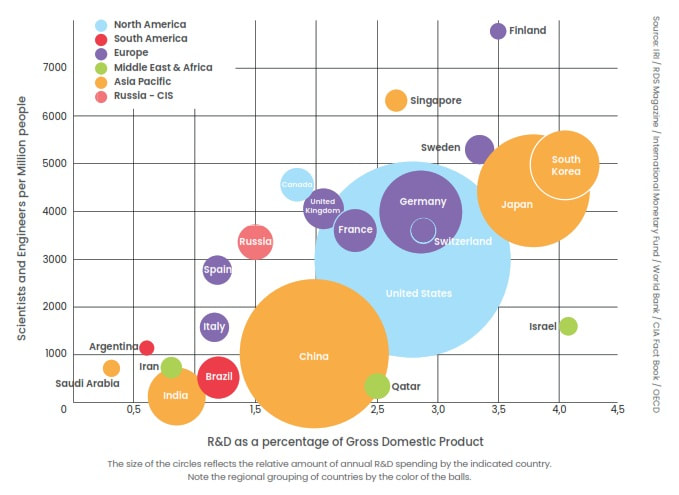

Innovation and the adoption of new technology by firms lowers the costs of production to firms, increases profitability and shifts the supply curve to the right in individual goods and services markets as more is produced and sold – increasing real GDP: ↑GDP = C + ↑I + G + (X – M). Governments can increase incentives to firms to invest in research and development programmes, for example, by offering tax credits for R&D programmes and ensuring that there is a labour force with appropriate skills for firms to engage in their R&D programmes. |

Improving competition and efficiency.

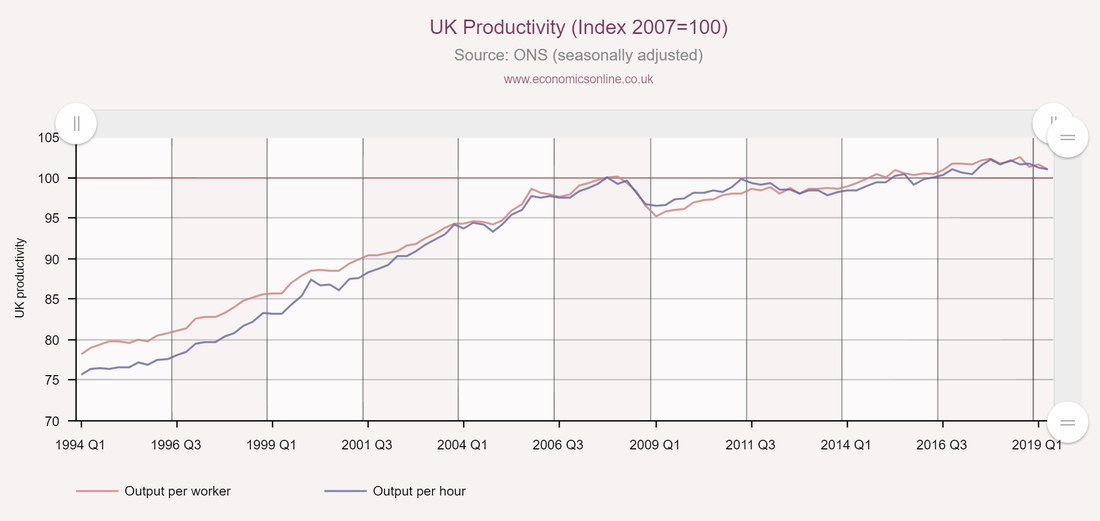

The aim is to increase the efficiency of firms to make them more responsive of firms to the market forces of supply and demand. An increase in productivity means that more can be produced with less. Productivity is the ratio between the output volume and the volume of inputs. In other words, it measures how efficiently production inputs, such as labour and capital, are being used in an economy to produce a given level of output. Reducing labour costs and unemployment through labour market flexibility.

Labour market flexibility refers to how quickly a firm responds to changing conditions in the market by making modifications to its workforce. A flexible labour market allows employers to make changes because of supply and demand issues, the economic cycle, and other market conditions. Increased labour market flexibility reduces unemployment and the cost of labour to firms – efficiency increases. Reducing inflation to improve international competitiveness.

As LRAS increases the price level decreases. Over time, goods and services produced in a low inflation economy will become relatively less expensive than those produced in countries with a higher rate of inflation. This means that, firstly, domestically produced goods and services will be relatively less expensive than equivalent imports, reducing imports and increasing GDP: ↑GDP = C + I + G + (X – ↓M). Secondly, exported goods and services will be more competitive in overseas markets, increasing exports and boosting GDP: ↑GDP = C + I + G + (↑X – M). |

Market-based supply-side policies

|

There are three categories of market-based supply-side policies:

ENCOURAGING COMPETITIONSupply side policies in relation to encouraging competition:

Antitrust laws prohibit agreements in restraint of trade, monopolisation and attempted monopolisation, anticompetitive mergers and tie-in schemes, and, in some circumstances, price discrimination in the sale of commodities. There are three main elements to antitrust or competition law:

A business with a monopoly over certain products or services may be in violation of antitrust laws if it has abused its dominant position or market power. Although not all anti-competitive behaviour which is subject to antitrust laws involve illegal cartels or trusts, the following types of activity are generally prohibited:

CHINA AND SUPPLY-SIDE POLICY

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

INCREASING INCENTIVESEssentially, incentive-based supply-side policies aim to reduce taxes which improve the incentives of households and firms, consumers and producers. These include:

Labour market reformSupply side policies in relation to labour market reform:

The labour market |

Interventionist supply-side policies

Investment in human capitalInvestment in human capital results in increased real GDP as both government and consumption spending on education and healthcare boosts aggregate demand in the short-term: ↑GDP = ↑C + I + ↑G + (X – M). In the long-term, increased human capital – the quality and quantity of labour resources – shifts the LRAS curve (or Keynesian AS) to the right, increasing potential output.

Human capital is the collective skills, knowledge, and other intangible assets of individuals that can be tapped to create economic values for themselves, their employers, and/or their community. Most if not all businesses thrive on the collective talents of each and every one of their employees. Increasing human capital increases the productivity of labour - output per unit of labour input. Investment in human capital can be made through training and education, and by improving health services and access to health services. Training and education and human capital. A country can increase the quality of its labour resources by investing in education and training programmes. Education and training programmes increase the skills of the workforce and make labour more productive. When education is left to the free market it is over-priced and under consumed. Governments intervene and directly provide educational services by funding and/or subsidising schools, vocational institutions (such as polytechnics), and universities. In general terms, the better funded education services are the better the quality of such services, the more it is consumed, and greater value is added for every year spent in education. Governments can also provide and/or fund retraining programmes for labour that is made redundant and/or target up-skilling the long term unemployed. This includes schemes which subsidise firms that employ people who have been unemployed for long periods of time. Education also produces positive externalities which justify government intervention. Other interventions would include incentivising people to relocate to geographic areas where firms struggle to obtain labour; subsidising housing in areas where housing has become unaffordable – many large cities – for those earning lower wages, as well as public transport to these areas; government projects in areas of high unemployment; and providing information on job availability. Better health care services and improved access to health care services. Labour productivity is higher in healthy individuals and communities. With good access to quality healthcare, sick days are minimised, those carrying injuries get back to work faster, and healthy individuals are more productive when they are at work. This is not just physical health but mental health too. For example, depressed individuals tend to have lower productivity for a variety of reasons, including low energy levels, cognitive dysfunctions, and strained working relationships. Having good access to quality healthcare improves the quality of labour resources and increases an economy’s potential output. And, just as with education, there are many positive externalities associated with health care that justify governments intervening in this market. Industrial policies

An industrial policy or industrial strategy of a country is its official strategic effort to encourage the development and growth of all or part of the economy, often focused on all or part of the manufacturing sector.

The government takes measures aimed at improving the competitiveness and capabilities of domestic firms and promoting structural transformation. A country's infrastructure (including transportation, telecommunications and energy industry) is a major enabler of the wider economy and so often has a key role in industrial policy. Industrial policies are interventionist measures typical of mixed economy countries. Many types of industrial policies contain common elements with other types of interventionist practices such as trade policy. Industrial policy is usually seen as separate from broader macroeconomic policies, such as tightening credit and taxing capital gains. Traditional examples of industrial policy include subsidising export industries and import-substitution-industrialisation, where trade barriers are temporarily imposed on some key sectors, such as manufacturing. By selectively protecting certain industries, these industries are given time to learn (learning by doing) and upgrade. Once competitive enough, these restrictions are lifted to expose the selected industries to the international market. More contemporary industrial policies include measures such as support for linkages between firms and support for upstream technologies. Supply-side policies will influence the demand side of an economy; and demand-side policies can also impact on the supply-side of an economy. These are examined, in turn, below. |

Investment in technology: research and development

Investment in technology results in increased real GDP as investment spending on capital equipment such as information technology systems and robotics boosts aggregate demand in the short-term: ↑GDP = C +↑I + G + (X – M). In the long-term, the development and integration of new technology shifts the LRAS curve (or Keynesian AS) to the right, increasing potential output.

This is because new technology could be developed, which would increase productivity and lower costs of production in the economy, making production more profitable and therefore more output is produced at each price in markets where new technology is incorporated. Governments in many countries, especially developed economies, support their own research and development programmes (e.g., funding university research programmes) as well as incentivising private firms to engage in research and development programmes. Such incentives include granting patents to protect intellectual property rights and tax breaks. Again, R&D generates positive externalities of production, thus justifying government intervention. Investment in infrastructure

Infrastructure is the basic physical and organisational structures and facilities (e.g. buildings, roads, power supplies) needed for the operation of a society or enterprise. Much of which is physical capital such as:

Good infrastructure increases the productivity of businesses and lowers costs. For example, good roading and railways increases the speed of transporting goods to domestic and international markets. More output can be transported at lower cost – productivity increases. Another example is that good telecommunications networks enable faster communication and more efficient digital technologies. Much infrastructure can be classified as being merit goods or public goods, and this justifies government intervention. Governments can provide infrastructure directly, subsidise it, and/or partner with private sector firms to provide it. Investment in infrastructure results in increased real GDP as investment spending on capital equipment and government spending on operational costs: ↑GDP = C +↑I + ↑G + (X – M). In the long-term, the development and integration of new infrastructure shifts the LRAS curve (or Keynesian AS) to the right, increasing potential output. Why Infrastructure Matters

Human capital |

The overlap of demand-side and supply-side policies

Demand-side effects of supply-side policies

Market-based supply-side policies

Incentive based macroeconomic policies such as encouraging private firms to engage on research and development and/or lowering taxes on business profits increases investment spending by firms and increase productivity. This in turn will increase the LRAS or Keynesian AS, signifying an increase in potential output. However, this type of policy will also increase aggregate demand as investment spending is a component of aggregate demand: ↑GDP = C +↑I + G + (X – M). Likewise, a policy of tax cuts to incentivise labour to work more increases LRAS or Keynesian AS, also results in an increase in disposable income. Some of which will be spent, increasing consumption spending, and some of it will be saved allowing banks to increase business lending for investment projects – investment spending increases. Therefore, in addition to increases in LRAS there is an increase in aggregate demand: ↑GDP = ↑C + ↑I + G + (X – M). Interventionist supply-side policies Government intervention in investing in education, healthcare, infrastructure projects and research and development programmes increases both the quantity and quality of human capital and physical capital, in turn, shifting the LRAS or Keynesian AS, signifying an increase in potential output. Such government spending (e.g., healthcare) and investment spending (e.g., roading infrastructure) also provides a boost to aggregate demand, shifting the AD curve up and to the right: ↑GDP = C +↑ I + ↑G + (X – M). Thus, such interventionist supply-side policies have an impact on the demand side of an economy – LRAS or Keynesian AS increases and AD increases. Essential statement: Some demand-side policies, while aiming to effect aggregate demand, have supply-side effects that can impact on an economy’s long-term growth potential; i.e., shifting LRAS. Demand-side policies can contribute to economic growth by providing a stable economic environment, increasing private investment and both private and public R&D spending, improving human capital through health and education spending, and increasing productivity through infrastructure spending Productivity explainedImproving infrastructure

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Government support for R&D |

Supply-side effects of demand-side policies

Monetary policy

Monetary policy can influence potential output put because interest rates have bearing on the level of investment in an economy. The higher the rates of investment, the higher the increase in LRAS or Keynesian AS, and the higher the level of potential output. For example, if a central bank embarks on a programme of expansionary monetary policy by decreasing the average rate of interest and increasing the money supply, firms will increase their investment spending because it is now less expensive to finance their investment projects. New, more efficient, plant and equipment will be introduced into current production processes and new production opportunities will be pursued. This increase in investment results in increases in the quality and quantity of physical capital, driving the productivity gains that increase an economy’s potential output. The opposite applies to contractionary monetary policy. Contractionary monetary policy will cause investment to contract and decrease an economy’s potential output. Thus, there is a supply-side effect to monetary policy demand-side management of an economy. Fiscal policy Like monetary policy, fiscal policy targets short-term demand management. Like monetary policy, effective fiscal policy can also provide a boost to the long-term potential output of an economy. There are direct and indirect effects that fiscal policy has on an economy’s potential output. Indirect effects of fiscal policy on potential output. A stable economic environment with low and stable rates of inflation and consistent economic growth without large or frequent swings in economic activity (the business cycle) enables both consumers and businesses to plan and perform economic activities such as producing, investing, consuming and saving. Investment in capital goods by firms and the development and adoption of new technology is the key to increasing the potential output of an economy. This can be shown in the business cycle, or as an increase in the production possibilities of an economy (the PPC shifting outwards) and/or an increase in long-run aggregate supply (LRAS) in the AD/AS model of economic activity. Most investments and the research and development of new products are long-term projects for firms, and as such, require long-term planning and projections to be made by firms. Having a stable economic activity where tax rates, inflation, investment deductibles, etc. are consistent over time makes it less risky for firms to engage in investment and research and development. If having a stable economic environment leads to relatively more investment than having a less stable economic environment, then it follows that if fiscal can be used to stabilise economic activity, then investment will be relatively higher and so too will potential output over time. Direct effects of fiscal policy on potential output. In addition to stabilising the economic environment → increasing investment → increasing potential output, fiscal policy can directly affect the level of potential output, by:

|

EVALUATING SUPPLY-SIDE POLICIES

ADVANTAGESThe advantages:

Essential statement: In sum, supply side policies can be very beneficial. However, in practice it is not always so easy to increase productivity. Also, there is a limit to how much benefit they can give, it is often more appropriate to use demand side policies. |

DISADVANTAGESThe disadvantages:

|

SUPPLY-SIDE POLICY FAILURE!

Question: Why were the supply-side policies enacted in Kansas such a failure?

|

BUSH'S SUPPLY-SIDE PROPOSALS

Question: Outline the advantages and disadvantages of supply-side policies in President Bush's budget proposal.

|

IB Economics 3.15 Supply-side policies

Summary Notes

IB Economics: 3.15 Supply-side policies teaching and learning PowerPoint notes for HL and SL IB Economics.

PROGRESS CHECK - TEST YOUR UNDERSTANDING BY COMPLETING THE ACTIVITIES BELOW

You have below, a range of practice activities, flash cards, exam practice questions and an online interactive self test to ensure you have complete mastery of the IB Economics requirements for the 3.15 Supply-side policies topic.

USE THE FLASHCARDS IN ALL THREE STUDY MODES

IB Economics 3.15 Supply-side policies

|

IB Economics 3.15 Supply-side policies

|

IB Economics interactive QUIZZES AND TWO CLASSROOM GAMES

Test how well you know the IB Economics 3.15 Supply-side policies topic with the interactive self-assessment quizzes below. Each interactive quiz selects 30 questions at random from a much larger question bank so keep on practicing! Aim for a score of at least 80 per cent

|

Loading 3.15A Supply-side policies

|

Loading 3.15B Supply-side policies

|